Yasujiro Ozu

Yasujiro Ozu

In 2010, I embarked on a quest to explore the entire filmography of Yasujiro Ozu in chronological order. The aim was to not only revisit favorite films by the Japanese cinematic master, but to also fill myriad knowledge gaps for myself within the career of one of my favorite directors.

That series was abruptly cut short in no small part due to the massive life change that is switching careers (and my subsequent departure from Hollywood Elsewhere).

A few days ago, Sight & Sound's 2012 edition of their once-a-decade poll of critics found two of Ozu's films among the top 20 most voted by critics as being among the ten greatest films ever made. Ozu's Tokyo Story is most often cited as constituting his greatest achievement. There it was at #3, right behind Citizen Kane. We'll debate the validity of things like list-based rankings until the end of time, but I thought now would be a great opportunity to re-launch the long-planned, "remastered" version of my series on Ozu.

So, welcome to Discovering Ozu (use #DiscoveringOzu when linking on Twitter).

Think of this series of articles as the travelogue of one cinephile's journey through the cinema of Ozu.

I don't purport to be a categorical expert on the man or his films, so please don't misconstrue this as me saying I could write some sort of definitive reference. For that, see David Bordwell's "Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema" (available as a 400MB PDF download at that link), which is my primary reference tome, or Donald Richie's equally great "Ozu: His Life and Films". More on both of those wonderful scholars as we go.

All currently-available Criterion disc releases of Ozu's films.

All currently-available Criterion disc releases of Ozu's films.

Discs, Streams, and Bootlegs

I'm blessed that the great people at The Criterion Collection have released the majority of Ozu's movies on DVD (and one on Blu-ray very recently). I own every single one they've put out, and paid for them myself (with the exception of The Only Son/There Was a Father, which I was sent a review screener for).

Since two years ago, Criterion has moved their catalog from Netflix to Hulu Plus, and various movies available on SD DVD from Criterion are viewable in glorious HD here. They also started selling SD and HD downloads of various movies on iTunes. I'll be touching on those additional viewing options in this run on the movies of Ozu with a new "How Do I Watch?" matrix.

The surviving films not released by Criterion all exist on Japanese or British DVD in one form or another. The BFI started releasing some outstanding Ozu double feature sets just as my original pass on this series ended. The Blu-rays are all Region B locked (won't play in US players), but I've invested in a player that can run them and tossed them all into my Amazon cart so that I can include coverage of them in this series. The cost of doing this is prohibitive for the average casual collector, but this is something I've budgeted and saved for in the way that some people plan lavish vacations or booze-soaked trips to Vegas (read: very intently).

Some Ozu films are much harder to come by than others, and while I do not endorse piracy, I recognize that bootlegs (sometimes the same thing as "imports" depending on the country) are often the only way to see some movies. Every bootleg I've seen of Ozu's otherwise-unavailable work has been absolutely abominable in terms of picture quality, and (as I'll write) should be avoided in favor of a legitimate release.

Changes

I'm adding more indexable info matrices than I used in my first pass at Ozu, including more detailed lists of where you can find what ("How Do I Watch?"). The first post in Discovering Ozu is a constantly updated series-spanning index that also lists Tag categories for key players in the Ozu world, from actors to writers to cinematographers and so on.

I've decided to continue using the American style of firstname-lastname formatting, just as I did the last time. I know that it is "wrong" all around, especially since I've always formatted Chinese names lastname-firstname. This makes me a terribly irreverent, disrespectful clod.

In terms of common usage, I've found all Japanese names in American pop culture (and even academic literature) to be done the Americanized Bastardization manner. For my purposes, I'd feel pretentious trying to write names in a way that isn't natural to me or the way I see them generally formatted.

The Man (Abridged)

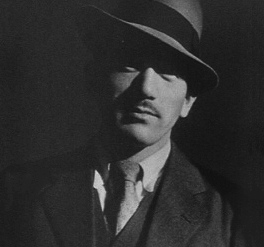

This is the photo of Ozu that I feel best evokes his independent spirit and enigmatic aura. Is he just an ordinary man in a sharply-tailored suit, or is he The Devil? Is he merely staring into the camera lens, or can he see your doubts and insecurities? Then again, is he anything or nothing in the first place?

These are examples of the thick philosophical knots into which I am tied by his quiet dramas.

I share the opinion of David Bordwell, Elvis Mitchell, and many other critics that Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) is one of the greatest directors that cinema has ever seen.

His film work spanned 35 years (1927-1962) and over 50 films, from silent to black & white talkie and finally to color. His career crossed the pre and post-WWII era in Japan, and saw lengthy notable gaps (1937-1941 and 1942-1947) as a result. The largest volume of his greatest films come after the war, though his first major commercial success came in 1932 (I Was Born, But...).

He never married and never had children. It is rumored that he may have once proposed to one of his actresses.

Tokyo Story (1953), his most-celebrated film, follows an elderly couple visiting their children (who treat them like an imposition). He died of cancer on his 60th birthday just before his final film (An Autumn Afternoon) debuted at the New York Film Festival in 1963.

His grave reads simply "mu" ("nothingness"), as can be seen in Wings of Desire director Wim Wenders' Tokyo-Ga, included in full on Criterion's release of Ozu's Late Spring (1949).

He lived with his mother until her death in February of 1962.

He began his career as an assistant camera operator for Shochiku. He did not take on directing his early films voluntarily, believe it or not.

The "180 degree rule" did not exist in Ozu's filmmaking methodology as a director. He felt no need to pledge himself to the religion of an imaginary line that requires all of his shots to match angles when cutting from one person in a conversation to another. Contrary to the opinion of most film school professors, this does not make his shooting continuity confusing or jumbled whatsoever. Forty years of austere English period dramas could have put less people to sleep by employing such a technique.

His filmography focused so intently upon tradition and modernity coming to blows that just as many scholars and critics who love him will line up to assert that Ozu made the same film over and over. Of course, the same could and has been said of various other great directors.

His early films lean more toward "entertainments" and overt comedies, but they retain Ozu's signature social conscience, even in the movies that he disliked making. In this respect, Ozu's couldn't be more different than American films from the same era.

The best-known Ozu films come from his domestic dramas made just before, during, and after World War II. What can be overlooked too easily by the dismissive is that his style is all about honing and precision. Radical, showy gestures and pageantry have no place in his kitchen. If his films are a set of implements, there are no cleavers or tenderizers, just paring knives.

As a whole, Ozu's films are a great testament to how storytelling in all forms owes so much to the oral tradition, wherein familiar elements are reworked over time to meet the evolving needs of civilization. His subtlety and poetic style are still so much more affecting than most of our modern films (made at many times his budgets) nearly half a century after his death.

Ozu and Me

I was first exposed to Ozu's work through the Criterion Collection DVD of Good Morning (1959, a relatively late Ozu film), which I picked up my senior year in high school.

I enjoyed Good Morning, but I didn't revisit Ozu for a couple of years, when I discovered Tokyo Story and Floating Weeds in college.

The 2003 release of Tokyo Story was the gateway drug to 2004's Floating Weeds set, which I was drawn to by the Roger Ebert commentary track. He is one of the best "film scholar" commentarians out there. Out of the various yack tracks he's contributed to, this one is my favorite, closely followed by Citizen Kane. I like it enough that I've decided to specifically dedicate a supplemental entry in this series to Ebert's Weeds musings.

As for the movies, the themes of traveling and generational strife really hit home for me, since I was 1,000 miles from home for the first time in my life. The few times that I would visit my parents' house in those first years were always odd. I felt as if back in a comfort zone, yet at once an intruder or a prisoner in some respect.

These aren't terribly unique feelings amongst those who go away for school, but it struck me as an interesting reverse parallel to the plot of Tokyo Story.

I could empathize in an odd way with the elderly parents who go to visit their children. Mom and Dad are made to feel as if they are more an inconvenience than a welcome, deeply-loved presence. I'm not saying that I was unwelcome in any way at my parents' home, not at all, but being disconnected from the household transforms you into a visitor, no matter how integral a part of the household you once were. Bonds of kinship mutate as a result, and interpersonal relations are transformed, sometimes in jarring ways.

These simple but profound changes are at the core of what interests me the most in Ozu's films. From an anthropological standpoint, his films are an essential part of the Japanese cultural record, bridging the silent-to-sound and pre-to-post WWII gaps.

His particular perspective on how the Japanese family evolved and coped with change during these periods is unmatched by his peers, from what I've seen and what others have written.

The thing that hooked me then and now was his choice to do things in strikingly different ways than everyone else. He made decisions to tell the story that he wanted to tell in the most compelling way possible. Not only is that admirable, but it really works.

Next in Discovering Ozu

A look at 1929's Days of Youth and the rest of Ozu's first eight films, seven of which have been lost. Ozu considered this no great loss.

Discovering Ozu is an ongoing series of articles designed to introduce curious cinephiles to the work of Japanese master filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu. The complete index for these articles can be found here.

Essential sources include: David Bordwell's book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, Donald Richie's Ozu: His Life and Films, and the various booklets and featurettes produced by The Criterion Collection. Quick reference often comes from definitive Ozu fansite "Ozu-san".

If sharing or discussing this article or series on Twitter, please use hashtag #DiscoveringOzu